Early Loading In Professional Sports

Paolo Policastri

In the past few years talking about rehabilitation, early loading (EL) became very popular both in literature and in everyday practice.

EL in musculoskeletal rehabilitation is the application of mechanical or functional load (e.g. passive movement, active exercises, weight‑bearing) relatively soon after injury or surgical intervention, earlier than conventional timelines of immobilization or complete rest, with controlled and progressive intensity matched to the healing stage, aiming to reduce adverse effects of disuse (atrophy, stiffness) and to promote optimal healing and functional recovery, while minimizing risk of re‑injury or delaying tissue repair.

Over the past two decades, the NBA has undergone a seismic shift in its approach to player health, care and performance. The emergence of integrated performance teams, comprising physical therapists, athletic trainers, strength and conditioning coaches, performance nutritionists, sports psychologists, and sports scientists, reflects a growing recognition of the interconnectedness of disciplines.

Kobe Bryant fractured a bone in his right hand during the early part of his third season in the NBA and missed fifteen games.

This paradigm shift aligns with the concept of ‘marginal gains’, where small, incremental improvements across multiple domains compound to yield significant results. Kudos to Sir David Brailsford from the ‘Team Sky’ days in elite cycling and the Tour de France, for bringing this concept to the forefront of performance in sport (the team used to bring the cyclists pillows on ‘away trips’ to help improve sleep and circadian rhythm setting, pretty much a relatively common practice now). Every 1% adds up. It’s how one approaches the small bits that speaks volumes about the big bits. For NBA franchises, the integration of these different skillsets and disciplines means not just preventing injuries - but optimizing recovery strategies, performance systems, and mental resilience programs.

Image generated using information from Christensen et al. (2020)

In this model, the PT occupies a unique position. Their role extends beyond rehabilitation; they act as a ‘bridge’ between medical care, and performance optimization. They often serve as the connective tissue (pun intended) that aligns the goals of diverse professionals within the team, and front office. More often than not, they can ‘speak the language’ of each discipline due to their backgrounds.

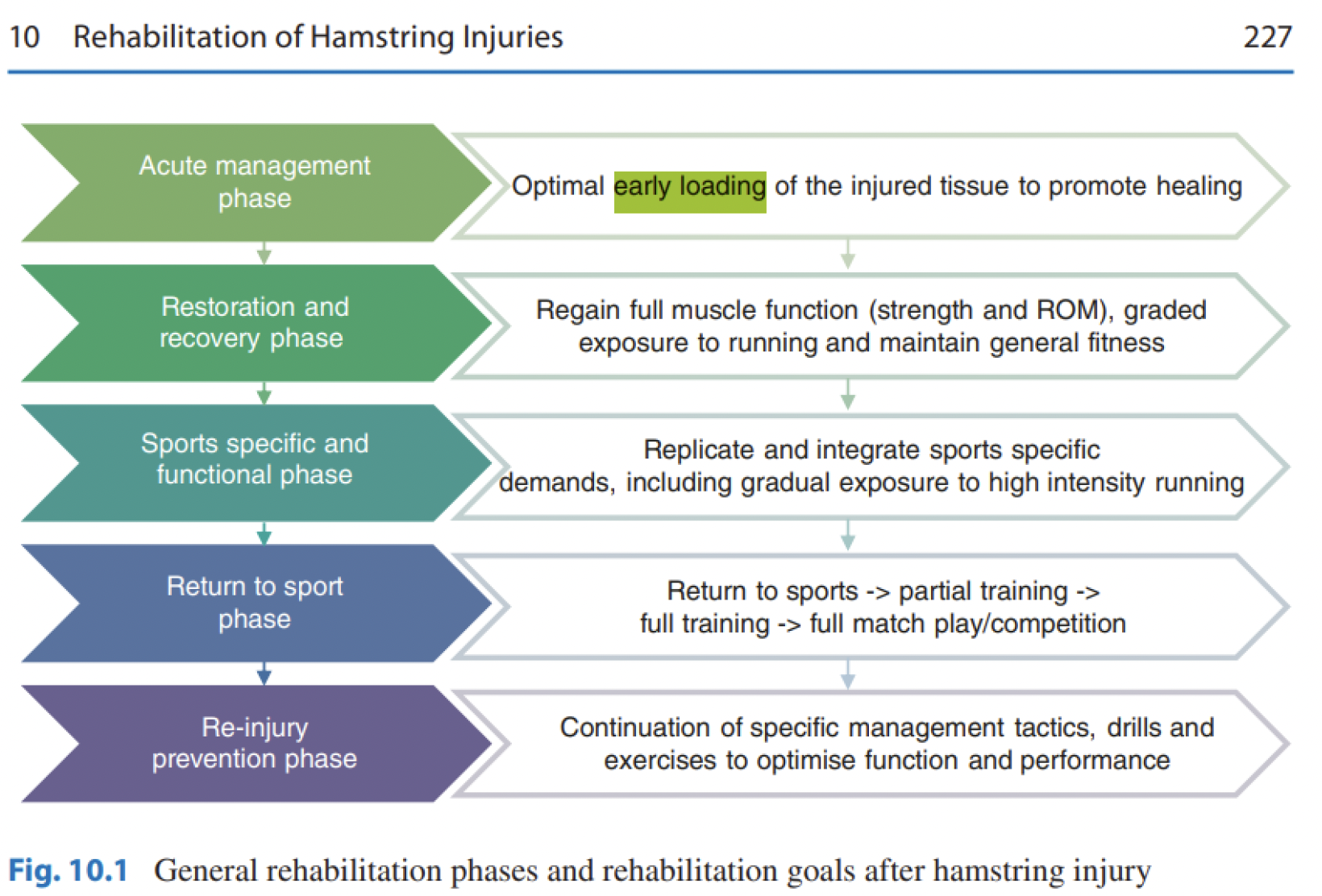

In literature, EL is not an universal word to define this approach, early functional rehabilitation (EFR), early mobilization and early weightbearing are also used. Following soft tissue injury, Bayer & Järvinen (2017) define early loading rehabilitation (ELR) as the recruitment of the injured tissue after 48h (2 days) from the traumatic event. In the same paper, delayed loading rehabilitation is defined as an intervention after 9 days from injury. Christensen et al. (2020) gives the reason why early loading, also called early functional rehabilitation (EFR), is important in rehabilitation: it helps to minimize the deficits caused by immobilization. In addition to that, Christensen et al. (2020) highlight the fact that EFR as part of nonsurgical treatment for Achilles tendon rupture was

Bayer & Järvinen (2020) mentioned in their work that early loading onset after the hamstring injury probably contributes to improving stability of damaged MTJ components post injury.

From Bayer et al. (2020)

A systematic review and metanalysis conducted by McCormack & Bovard (2015) found that EFR is safe and patients report higher satisfaction.

Early postoperative weightbearing with less rigid immobilization appears to accelerate short-term functional recovery after Achilles tendon repair (Gould et al. 2021, Wang et al. 2024).

Surgeons have historically been hesitant to allow early load bearing after lower extremity fractures to limit risks of loss of reduction and implant failure (Hoyt et al. 2015). While orthopedic device constructs and physiologic theory support early weight bearing, many providers remain hesitant to this approach (Hoyt et al. 2015). When talking about lower limb fractures, the use of progressive but restricted weight-bearing protocols would seem a viable compromise (Hoyt et al. 2015).

Following Sharma & Farrugia (2022) on considering the benefits observed with early weight- bearing in post-operative management of ankle fractures, the result may be partly explained from a physiologic standpoint as early weight bearing has been shown to reduce calf atrophy and decrease osteoporotic changes. Continuous passive motion (CPM) is a form of early postoperative mobilization used to reduce the development of stiffness after lower extremity injuries (Hoyt et al. 2015). Controlled but appropriately aggressive early mobilization with progressive weight bearing is indicated for patients with lower limb traumas (Hoyt et al. 2015).

Wang et al. (2024)

Hickey et al. (2022) suggests that in hamstring rehabilitation eccentric loading can be safely progressed based on individual exercise performance, regardless of pain and between-limbs strength deficits during isometric knee flexion after acute hamstring strain injury (HIS), and this progressive approach to eccentric loading has been shown to increase hamstring strength and long head of the biceps femoris muscle fascicle length in relatively brief periods of rehabilitation after acute HSI.

Dhillon et al. (2017) enhance the importance of early mobilization and tissue loading to promote collagen reorganization and tissue healing. They suggest incorporating early in the rehabilitation sports-specific speed, strength, agility, and flexibility drills that have proven to be effective in the initial stages in avoiding overall deconditioning and positively affecting return to participation. At the same time, progressive load plays a key role in an efficient return to play (RTP) process.

Controlled early eccentric loading is suggested by Hickey et al. (2022) as well as tolerated running technique drills after hamstring injury.

In modern competitive sport, injured athletes are under pressure to return to competition as soon as possible (ASAP), which is often a demand for both the athlete and the Club.

So, why early loading is important?

It helps us to reduce the duration of player’s unavailability. With early loading we can start doing things that we will do it in any case during the RTP process. The management of a professional athlete is in some ways the same as of a normal patient. The urgence to be back to work is the same: ASAP. The good thing on athlete’s management is that we can have a day-to-day control on him/her, and being back to work for them is strictly related to the injury. With normal people, for example talking about a painter, a HIS won’t stop him from doing his/her job and it is too expensive for him/her doing therapy every day without going to work (depending on healthcare system), so there is no 100% control on this kind of patients.

The day-to-day treatment and follow-up on a professional athlete help the professional to promote early loading. Every clinical case is different, but choosing of doing plyometrics after 2 days from a calf injury is not part of the risk of early loading but is more a lack of competence of whom is taking care of that player.

So, what is the risk of early loading? First, healthcare is different in professional sports, pro athletes needs staff that are well prepared to work at that level and with a particular mentality. However, implementing any rehabilitation intervention requires careful consideration of factors both intrinsic (eg, age and injury history) and extrinsic (eg, pressure to expedite RTP) to the athlete. Pain is the most used scale of evaluation in early stage rehabilitation and talking about early loading, a score of 3-4/10 (VNS) of pain is clinically acceptable in the initial phase. Pain doesn’t mean damage, so early loading itself it doesn’t depends on the tissue, but on the stimulus at which the tissue is exposed. It’s more dependent on the Professional and his/her treatment proposal, because in the early stage the athlete is highly dependent on the Physiotherapist.

Planning, competence and knowledge must be the basics of every professional, especially when applying EL.

In a psychological point of view, early loading gives hope and trust to the player. An injury can have catastrophic consequences on a player: imagine if an injury occurs 2 months before the end of the season and the player has important matches to play or his/her contract is expiring. They need to play and they want to play, their professional life is depending on this. Early loading tells the player that we are really doing our best to get them back. They realize that we want the same, being back ASAP. Trust is crucial in the success of a rehabilitation program, and we have to do everything we can to gain it with our players.

Curiosity and reflection are fundamental in this process, because curiosity drives the urge to find new ways of treating an injury, the need to find something new to reduce the unavailability time, and reflection is the step after to process the new information and think about the practical application in that specific situation.

In the end, early loading is just the ability to not let our players being too much detrained. Rehab is always training in the presence of an injury and applying early loading is just the practical application of it. The more we can do from the beginning, the better will be after.

On player’s perspective, the early they start working, the early they forget the moment of the injury and start thinking about the future, the next game they’ll be available. Indeed, early loading projects the player to the future, open the space for optimism leaving the bad memories of the injury behind.

References

Hoyt et al. 2015; McCormack & Bovard 2015; Bayer et al. 2017; Dhillon et al. 2017; Bayer & Järvinen 2020; Christensen et al. 2020; Gould et al. 2021; Hickey et al. 2022; Sharma & Farrugia 2022; Wang et al. 2024

Bayer ML & Järvinen TAH. (2020). Basic Muscle Physiology in Relation to Hamstring Injury and Repair. In Prevention and Rehabilitation of Hamstring Injuries, ed. Thorborg K, Opar D & Shield A, pp. 31-63. Springer International Publishing, Cham.

Bayer ML, Magnusson SP, Kjaer M & Tendon Research Group B. (2017). Early versus Delayed Rehabilitation after Acute Muscle Injury. N Engl J Med 377, 1300-1301.

Christensen M, Zellers JA, Kjaer IL, Silbernagel KG & Rathleff MS. (2020). Resistance Exercises in Early Functional Rehabilitation for Achilles Tendon Ruptures Are Poorly Described: A Scoping Review. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 50, 681-690.

Dhillon H, Dhillon S & Dhillon MS. (2017). Current Concepts in Sports Injury Rehabilitation. Indian J Orthop 51, 529-536.

Gould HP, Bano JM, Akman JL & Fillar AL. (2021). Postoperative Rehabilitation Following Achilles Tendon Repair: A Systematic Review. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev 29, 130-145.

Hickey JT, Opar DA, Weiss LJ & Heiderscheit BC. (2022). Hamstring Strain Injury Rehabilitation. J Athl Train 57, 125-135.

Hoyt BW, Pavey GJ, Pasquina PF & Potter BK. (2015). Rehabilitation of Lower Extremity Trauma: a Review of Principles and Military Perspective on Future Directions. Current Trauma Reports 1, 50-60.

McCormack R & Bovard J. (2015). Early functional rehabilitation or cast immobilisation for the postoperative management of acute Achilles tendon rupture? A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Br J Sports Med 49, 1329-1335.

Sharma T & Farrugia P. (2022). Early versus late weight bearing & ankle mobilization in the postoperative management of ankle fractures: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Foot Ankle Surg 28, 827-835.

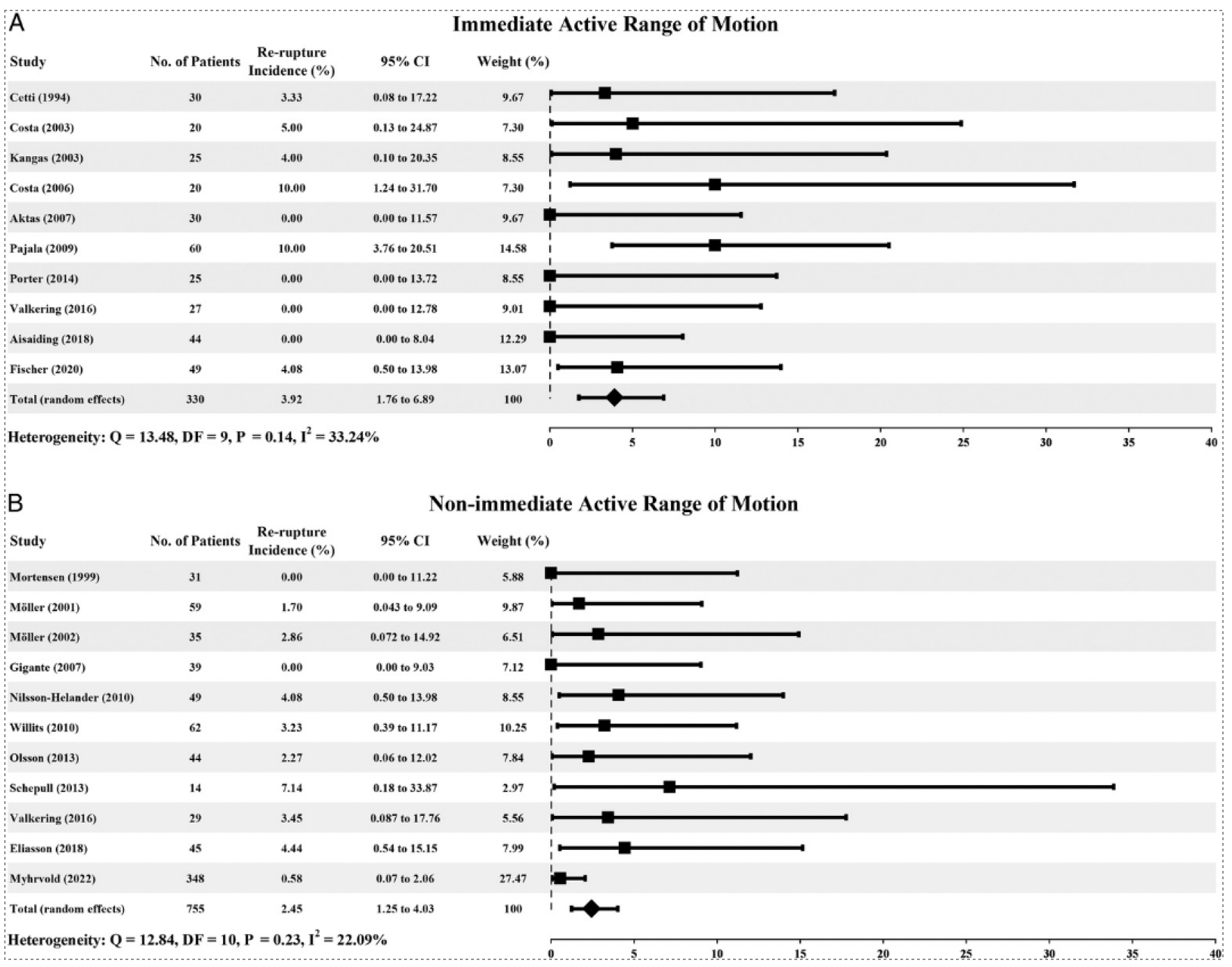

Wang R, Huang L, Jiang S, You G, Zhou X, Wang G & Zhang L. (2024). Immediate mobilization after repair of Achilles tendon rupture may increase the incidence of re- rupture: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. International Journal of Surgery 110, 3888-3899.

About The Author

Paolo Policastri

Hi, my name is Paolo Policastri and I’m an Italian sport physiotherapist and osteopath. I come from Cittadella (Pd), a small town in the north-east of Italy, famous for its ancient round walls (800 years old!). My Family (my parents and two older brothers) lives there.

Basketball has always been my passion and my relief valve especially through my adolescence, I’ve played from 6 to 31 years old. I’ve lived in Conegliano, Milan, Bruxelles, Dublin, Parma and nowadays I’m in Sion (Switzerland). I am a learner, ambitious, curious and reflective person. Respect, loyalty, listening, fairness and empathy as the essential 5 I strive to live by each and everyday. One of my favourite things is to challenge myself, to share knowledge and meet new professionals and learn from their experience.

So far, I’ve worked in professional soccer and rugby with different clubs. To date, I am the Head of Medical at FC Sion (Switzerland, soccer). I’ve worked in private clinics and in professional sports, and I prefer the latter because it’s more dynamic, I love being part of a team, share feelings and challenges and help professional athletes to achieve their best. I’ve been part of different projects and the one I’m most proud of is that I’ve contributed to the writing of a chapter of a book entitled ‘Essential Skills for Physiotherapists’ (Elsevier, 2024).